By Felicia Wetzig

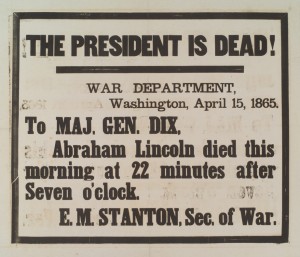

The joy the North felt when the war ended was brought to a rude halt on April 14, 1865. While President Lincoln and his wife, Mary, were enjoying a performance of “Our American Cousin” at Ford’s Theater, he was shot by John Wilkes Booth and died the next morning.

The Lincolns were accompanied to the play by a young army officer who immediately tried to apprehend Booth and was stabbed in the shoulder. Booth jumped from the booth onto the stage, breaking his leg in the fall. Before he limped out of the theater he shouted, “Sic semper tyrannis!” (“Thus ever to tyrants!”).

The President needed immediate medical help.

A young doctor just two months out of medical school, Charles Leale, immediately rushed to the president’s side. Lincoln was carried to a house across the street, and was attended by a number of doctors, all of whom agreed that Lincoln’s wound was fatal and he would die within the night. At 7:22 the next morning, he was pronounced dead, and his body was placed in a temporary coffin draped with a flag and taken to the White House. News of the president’s death spread quickly, as those who had been rejoicing over the end of the war were thrown into turmoil at this shocking turn of events.

Dr. John Morris and his younger brother, Julius, both of Kent, were present at the theater on the night of Lincoln’s assassination. Dr. Morris had served as a surgeon in Washington, D.C. for most of the war and had met Lincoln at least twice. On the evening of the performance, they were informed that the President would also be attending. Years later, John Morris recalled the evening:

The Lincoln Assassination

“My brother and I chose seats where we could see the vestibule where the Lincoln’s were to be seated. When the President entered the theater, the leader of the orchestra, signaled ‘Hail to the Chief.’ The audience then caught sight of the President and, rising as a body, cheered again and again. . . . About midway through the performance with my attention upon the play I heard what I believed was a door slammed shut. Not realizing what happened, my brother and I remained seated.

“Just then we looked up and saw a man vault over a railing and seemed to lose his balance and fall awkwardly on stage. The man quickly regained his footing and flourished a dagger, shouting something about tyrants and then dashed across the stage and out the north side of the theater. Standing up, I could see Mrs. Lincoln holding something and screaming that the President was shot.

“Ford’s theater then became a scene of terror and pandemonium. . . My brother and I being in uniform tried to force our way to the stage where we might be of aid. Then, we noted Dr. Charles Leale making his way to the Lincoln box, so we knew Mr. Lincoln was in good hands.

“My brother and I remained outside Ford’s Theater until we learned the wound was mortal. Shortly after, we witnessed the procession carrying the body with Dr. Leale supporting the President’s head and crying like a baby. Thus Abraham Lincoln began his final journey in life. I know, because I was there. A horrible spectacle I carried with me all the days of my life.

William E. Broadhurst, of Kent, was also present at Ford’s Theater on that night, after serving three years with the Union army. Broadhurst and another soldier had stepped out of the theater between acts to have a smoke, but when they tried to return, the doorman refused to readmit them because the president had been shot.

Matilda Morris, a nurse from Randolph, was working in a Washington, D.C. hospital. She wasn’t present at the theater, but she recalled the shocking news as it spread through the capital.

“[T]hen the bright future was suddenly overcast as Treason guided the assassin’s hand in its deadly work. The mighty had fallen – Abraham Lincoln, the noblest of martyrs, to a noble cause!”